By the time Michael Thomas heard the phrase “you should build a system that…” from his supervising attorney for the tenth time, what he decided to do next might be considered overkill.

Mr. Thomas, an office manager and paralegal at a small law office, spent years responding to recurring operational demands — improving intake, tracking deadlines, centralizing documents, and reducing duplication. Each request pointed to the same underlying problem: the office relied on fragmented tools and improvised workflows. There was no system in place, and the existing commercial platforms on the market were not a practical fit for the office. So, Mr. Thomas decided to build one.

He did not announce the effort. There was no budget, no development timeline, and no formal mandate. Instead, after office hours, Mr. Thomas began coding.

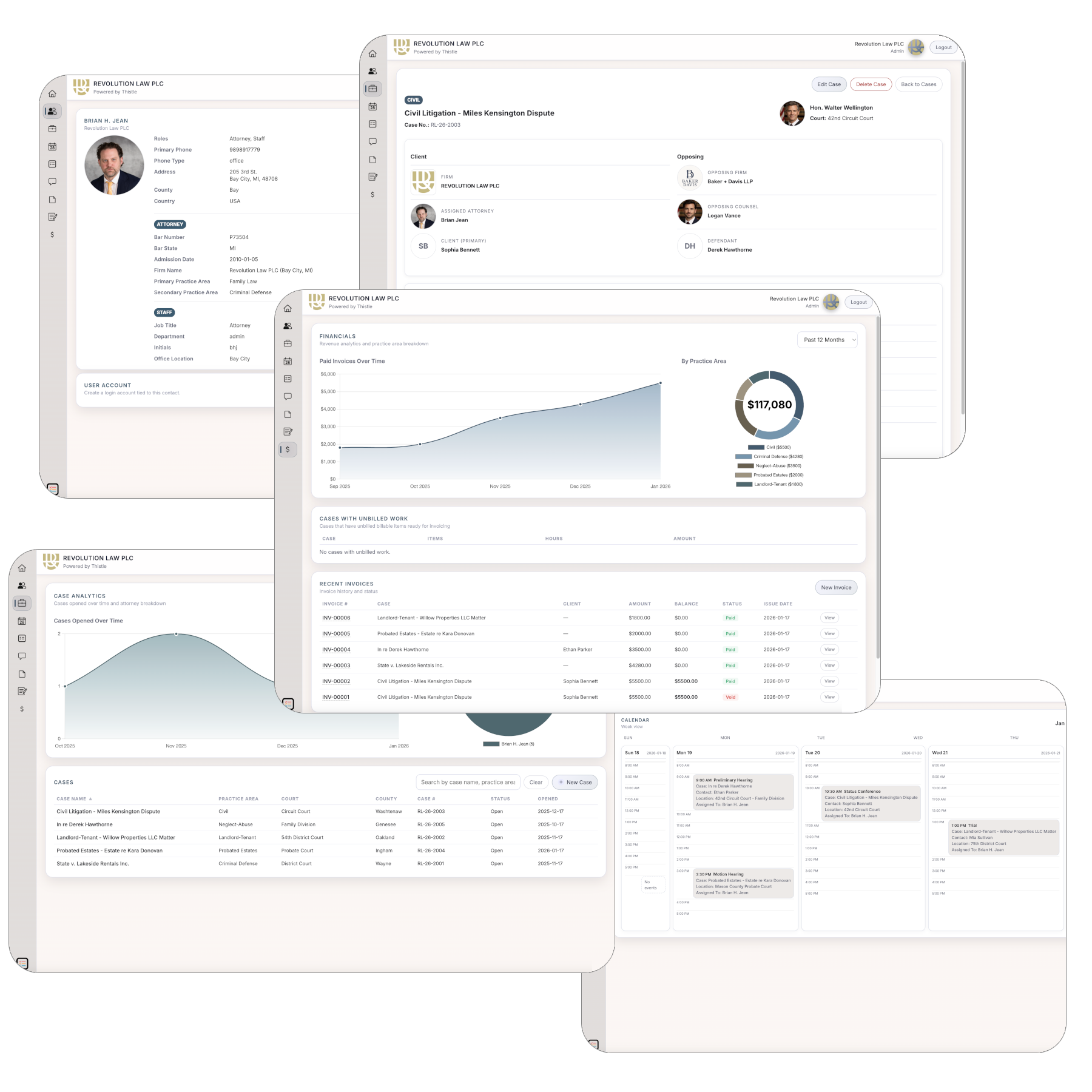

What started as an effort to bring consistency to case tracking gradually expanded into a full legal case management application. Working nights and weekends, he built the software incrementally, adding one section at a time. Client records came first, followed by cases. Then tasks, calendars, documents, communications, and internal notes. Each component was designed to function as part of a larger whole, with careful attention to how work actually moves through a law office.

As the system expanded, Mr. Thomas also began addressing a recurring source of disruption: routine client status inquiries. The platform includes a secure client portal that allows clients to view updates, documents, and case progress on their own time, reducing the need for frequent phone calls to the office. The goal, Mr. Thomas says, is not to limit communication, but to make it more purposeful — freeing staff to focus on legal work rather than constant status checks.

Mr. Thomas approached the project as an operations problem first, and a technical one second. The development process has been intentionally slow and methodical, with new features added only after existing ones are stable. Services are implemented cautiously, data structures reviewed repeatedly, and changes tested before moving forward. Progress is measured in reliability, not speed.

The application is being coded entirely in Mr. Thomas’s spare time — a boundary he has been explicit about. The project is neither a shortcut nor an experiment. It is a deliberate attempt to translate day-to-day operational strain into software logic, informed by direct experience rather than abstract design principles.

That experience shapes the system at every level. Mr. Thomas knows the day-to-day chaos of a law office firsthand: shifting deadlines, overlapping matters, constant interruptions, and the quiet risk created by disorganized information. The system was built inside that environment, not apart from it.

“The most effective research for Thistle, by far, has been its regular, day-to-day use inside a working law office,” Mr. Thomas says. “I can see very quickly what works, what slows people down, and what needs to be adjusted.”

In the coming months, Mr. Thomas plans to begin offering the application, which he calls Thistle, to other law firms in the area. His role places him in regular contact with paralegals and legal assistants at neighboring firms — professionals who face the same pressures and rely on similar informal workarounds. Those relationships provide a natural channel for sharing the system with others who immediately recognize the problems it is designed to address.

“The most effective research for Thistle, by far, has been its regular, day-to-day use inside a working law office,” Mr. Thomas says. “I can see very quickly what works, what slows people down, and what needs to be adjusted.”

As the project moves beyond personal use, Mr. Thomas has begun taking formal steps toward professional distribution. He is laying the groundwork necessary to offer the software in a responsible and sustainable manner. The shift reflects a change in posture — from an internal solution to a platform intended for broader adoption.

Thistle is not presented as a sweeping reinvention of legal technology. Instead, it is positioned as a system built by someone who understands how legal work actually gets done, and how easily it can break down without structure.

After eight months, the system is functional and expanding. It reflects a law office’s view of legal work: deadline-driven, detail-heavy, and intolerant of ambiguity. Where many off-the-shelf platforms impose rigid workflows, Mr. Thomas’ system mirrors how work actually moves through a small practice.

The irony is not lost on him. The instruction to “build a system” was never formally defined. It was repeated casually, almost offhandedly. Taken literally, it resulted in hundreds of hours of quiet, disciplined development — and the foundation of a tool he now intends to share.